PODCASTS / E109

Ep. 109 – Let’s Talk About The Dirty, Nasty P (Pricing)

January 1, 2024

There’s at least two ways that new CPG founders come to take retail pricing seriously, finally, once and for all.

The first way is after your first 3P distributor payment which is basically nothing after all those chargebacks and fees, fees that your product margin, in absolute pennies, can not in any way swallow up. If you net pennies per unit are 10 cents or less, I’m sorry, but your wholesale price is way, way too low. You failed the primary math test of retail consumer brands.

The second way new founders awaken to pricing problems is more common and just as bad but on the other end of the continuum. It’s the result of the artisan ego trap. It tends to happen to smart new founders who actually understand math and are terrified of not making money so much they incorrectly believe that they should be making a profit right away. In retail. This is how you get lovely folks with great products selling $15 jars of pasta sauce and wondering why the velocities crawl all year until after Thanksgiving. Ah, yes, the Q4 specialty foods trap is notorious for over-priced new brands.

I like the ambition of this second group and admire their desire to run a profitable business, but there really is something called way too high a price in your category.

Many founders who are new to third party, or mediated, distribution to retail get very lost in the markup math on the way to the shelf. I don’t blame them, because everything in your being wants to avoid the terrifying truth that the retailer, in general, takes half of the retail price for themselves. Yes, yes, they do. Then the distributor takes another 30%. You, the founder, make the least of anyone in the value chain to the shelf.

But wait. I’m not here to go over basics.

I’m here to talk about pricing power. Snore…

Some of my listeners are in finance, so I know haven’t lost everyone yet. Pricing power matters because, eventually, you want this power. It’s the power that allows you to command a price increase to keep up with inflation (even if your ARP is declining as volume moves proportionally through down market retailers). Starting out, you have no hope of getting a price increase to happen, because you have no volume, low velocities AND you’re nobody. If the distributor doesn’t block the price increase, your buyers will.

The retailer already wants your price lower than it is in most cases outside of the speicalty retail world. The last thing they will do in Phase 1 is let you raise it because you failed the mark-up online math course. Oops. No one cares, trust me. The line to replace you is long. This is why it’s much smarter to err on a case price that leads to a very high SRP…even artisan. Lowering it will still take some communications finesse with buyers so that either the distributor or the retailer don’t just pocket the extra margin pennies on your new, lower case price. They will, if you’re not looking.

But, farther up the Ramp, there IS the ability for you to command pricing power. Most consumer packaged goods categories have relatively inelastic demand, unlike the travel industry.

In fact, we just went through a crazy mass experiment in price inelasticity in CPG due to substantial unit price increases across the industry in 2022. Pricing power = relative inelasticity in price. If the price goes up, the quantity sold changes little. Huh? Say what? The power of your brand reveals itself in how little your volume changes with a price increase.

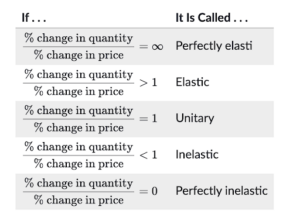

But let me explain this fancypants concept:

Price elasticity 101 for English and Anthropology Majors:

- measures the ability of a category of goods to sustain its current sales quantity (units, cases, liters, pounds, etc.) after changes in price

- an inelastic category of goods does not experience shifts in demand as supply changes

- Khan Academy breaks it down as follows.

For example, TTL food and beverage in MULO has had a low price elasticity of 0.2 in the past year (according to SPINS L52week, August ’23 data shared by the nice folks at Whipstitch Capital) despite the historically high price increases. This means that owners of iconic mega brands can (and do!) raise pricing dramatically to boost profits. But, if they slash them, demand won’t increase much. For every 10% price decrease, food/beverage demand will increase 2%. Woo hoo! If you’re in Phase 1, 2% baseline lift in sales will cause you to cry out in defeat. But not when you’re a $14B holding company.

However, there is significant variability at the brand level. The smaller the stream of goods, the more chaos there will be in elasticities. It may be impossible to really measure it well just like UPC data from SPINS is often subject to hallucination at small amounts.

Well-built premium-priced brands marketed to the right audience for everyday usage tend to be price inelastic as long as consumers do NOT think you’re interchangeable. This is where the scope of analysis matters. We all use gasoline—100% of us. Gas is not interchangeable as an energy source for personal transport. Not easily. Not for most of us (who don’t own EVs). Same with food. You will buy it somewhere. You are not a homesteader.

When we zoom to the brand level, wow, you become wildly interchangeable. Most consumer outcomes (e.g., energy, satiety, nutrition) have hundreds of solutions in the grocery store. In other words, the supply of brands wildly exceeds the demand for YOUR brand. Oops. This is why Liquid Death focuses almost exclusively on brand identity and can design to be SUPER memorable. Most water is sold purely on price, and people can’t remember the brand they drank two minutes after purchasing it from WaWa.

This is why you must build a branded relationship with fans who will pay a very high unit price early on. Creating an irrational burning need for your brand makes the oversupply disappear in the right consumer’s mind. And because slashing prices in food and beverage does not grow volume enough (when you are a $10m brand) for your P&L to look any different. If you are a $15 BILLION holding company, a 2% volume increase matters a lot and may allow you to re-negotiate your pricing on a core ingredient. This is why major brands have ruthless promo programs…to capture that 1-2% lift. This kind of ‘lift’ does not matter if you are a $5M start-up.

As I pleaded in Ramping Your Brand, the sadly weak volume effect of price promotions for small companies is why you MUST start selling at 50-200% above Oreo (but not any higher, or you will become a specialty gift), and once you get to say $100M, it is time to relax pricing steadily over years (if necessary) to obtain your 2-5% annual boosts of volume (which compound BTW very nicely).

Reducing price should be done at the SRP level, slowly, over years after hitting $100M…not through promos.

Pricing Power cuts both ways in CPG – you can price relatively high if you are not inter-changeable, but slashing your price (no matter how cool you are) is NOT how you scale.